November 3rd, 2019

There are so many privacy-enhancing extensions out there, it’s hard to keep track of which do what and where they overlap in functionality. Since an excess of extensions and plugins slows down your browser, I’ve decided to keep an updated list of what I recommend and use as well as the defaults that need to be changed. The following recommendations are as of October, 2019. I’m focusing on a relatively straightforward experience that doesn’t interfere with day-to-day surfing, break a lot of websites, or require extreme technical knowledge. (That is, no NoScript or GreaseMonkey.)

This article is primarily focused on desktop browsers. I might have more to say about mobile platforms in a future post.

tldr; Use Firefox 70 or later with these three extensions:

Read the rest of this entry »

Posted in Privacy | 1 Comment »

November 18th, 2017

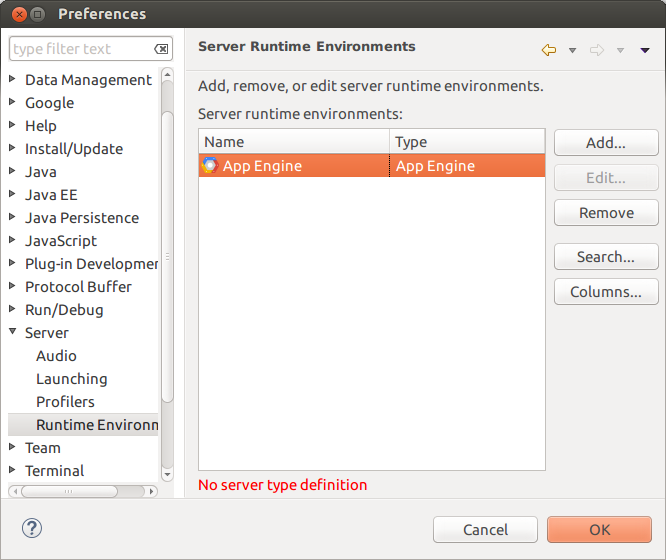

If you’re reading this, you’ve stumbled across the HTTPS secured and IPv6 enabled version of the Cafes. This has moved from a classic shared Linux server on pair.com to App Engine Standard on GCP. The transition is still in progress and was not without bumps.

Read the rest of this entry »

Posted in PHP, Web Development | 1 Comment »

February 8th, 2016

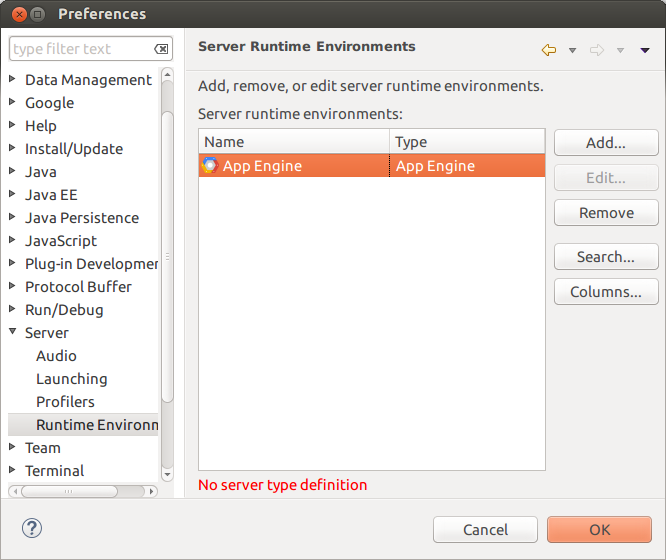

Here’s a red error message Eclipse popped up on my screen today:

There are a lot of things to complain about here, but the main one is not obvious from a static screenshot (though it turns out a static screenshot has exactly the problem):

The message cannot be copied.

Read the rest of this entry »

Posted in User Interface | Comments Off on Error Dialogs for the Internet Age

November 10th, 2015

Lately I’ve been working on a project that uses git as for storing source code. I’ve previously written the fourth edition of Java Network Programming in asciidoc with all files checked into git, but that was a very different experience: single author, no branches, always working against master. In other words, it was much like my experiences with Perforce, Subversion, CVS, and (this is really dating me) RCS.

The new project is more traditional git: many branches, many developers, many forks. Perhaps the git/bitkeeper distributed model makes sense for projects like the Linux kernel where there are many independent repositories on many developers’ machines, none authoritative. However for a traditional single team, single repository project, git feels far too heavyweight and complex for my tastes. I find it slows me way down. However like most developers I’m slowly getting used to it, and developing my own small subset of the vast corpus of git functionality that I actually use.

Git is designed to support frequent commits, and pass change requests back and forth as lists of commits so the development work is tracked, rather than by passing file diffs back and forth like most other systems. Now what really confuses me though is that no one seems to actually use it this way. if you want to submit a patch, you do not in fact send the list of commits that shows the history and ongoing work. Instead you rebase everything against master and send a single commit that squashes all the changes together, which seems to be exactly what git is designed to make unnecessary. In other words, we’re using git as if it were a traditional single-master system such as Subversion. Why? And does any project actually expect developers to send their full list of commits rather than a single squashed commit?

(Side note: Perforce is the best of both worlds here. To my knowledge, Perforce and its clones are the only version control system that manages to separate out the ongoing work in a change list and the final commit, and show you both depending on what you want to see.)

Regardless of the wisdom of discarding all history before submitting, like removing all the scaffolding before publishing a mathematical proof, it is how almost all git-based projects operate. Like most (all?) operations in git, it is far from obvious how to actually squash a series of commits down so it’s one clean diff with the current master. And also like most operations in git, there are multiple ways to do this. What follows is the approach I’ve found easiest and most reliable:

Read the rest of this entry »

Posted in Source Code Control | 8 Comments »

August 23rd, 2015

This morning BBEdit reminded me it was time to upgrade to version 11, but what really caught my eye was the copyright notice in the dialog box:

Copyright Barebones Software 1992-2015.

Has it really been more than 20 years since those early freeware versions on System 7? What is it about text editors that enables them to last so long? emacs and vi are even older.

This got me thinking. What software am I still using today that I was using 20 or more years ago?

Read the rest of this entry »

Posted in Software | Comments Off on Oldies but Goodies